Tags

alchemist, Alchemy, Ali Puli, Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica, Centrum naturae concentratum, Concentrated Centre of Nature, Esoteric Book Conference, gold, Lapidus, mercury, Paul Hardacre, Philosopher's Stone, Philosopher’s Mercury, salt, Salt of Nature, The Epistles of Ali Puli, The Pass-Keys to Alchemy

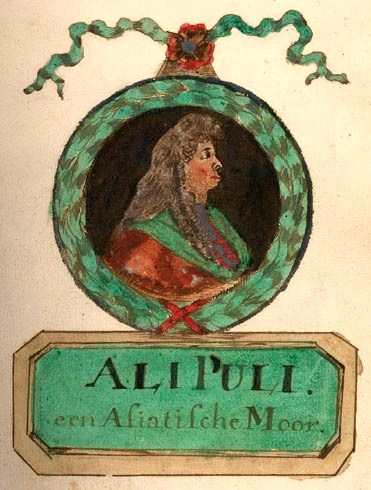

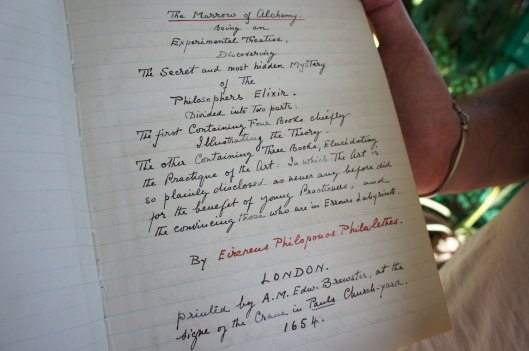

The second of Lapidus’ seven pass-keys consists primarily of lengthy extracts from Centrum naturae concentratum (or Concentrated Centre of Nature) by Ali Puli, The Asiatic Moor. Ali Puli was likely the nom de plume for Johann Otto von Hellwig (or von Hellbig), and the Centrum naturae concentratum manuscript – formerly owned and used by J.W. Hamilton-Jones for his 1951 translation into English under the title, The Epistles of Ali Puli (circa 1700 A.D.) – now resides in the Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica in Amsterdam.

Lapidus begins by writing that “Most books on the subject of alchemy are in agreement that the three main PRINCIPLES used to produce the Philosophers’ Stone are gold, mercury and salt. The metals gold and mercury are well known, but no book gives any idea what kind of salt is used, and rarely indeed where it may be found. However, one alchemist has ventured to disclose this, the greatest secret of the art. He has gone further by writing a treatise dealing only with this mysterious salt, and goes into much detail to describe it, and describes its virtue and power to act in the work to produce the Philosophers’ Stone, and even hints how to prepare it for use.” Lapidus is, of course, referring to the treatise by Ali Puli. Based upon his study of Ali Puli, Lapidus opines that “this salt is the basis upon which everything depends from beginning to the end” and that “without the aid of this salt, nothing can be achieved.”

Lapidus quotes Ali Puli at length:

Is it not wonderful that from plants, fruit and vegetables, all the things that go to build animal and human bodies, should be born and grow out of these, and even create living creatures, with the seed that can grow in them? Why then should Nature stop its work at metals? These gold, silver, lead, tin, copper, antimony, and iron, the metals also used the salt of Nature. The alchemists of old certainly did not agree that Nature stops at metals and worked on and laboured to prove it true, and so at length, succeeded, with the aid of the salt of Nature. With this knowledge they produced the Philosophers’ Stone … Search for this natural law, of salt of Nature, in your researches, for this is the greatest secret, and in all books of alchemy, hidden with the greatest care … The salt of Nature is found everywhere, and in everything. From all substances however, it is not easily to be obtained, nor is it sufficiently powerful for all purposes. For the often mentioned Masterpiece of the Philosophers, it is as good as for many things. But it is necessary to choose the best that can be found in Nature … When the Artificer knows how to extract from the world, its inner central force or Salt of Nature, and also knows where to find an abundance of the Salt of Nature united to the astral focal seat in anything … then the truth of Nature is resident in him, and with this illumination he can perceive Nature throughout. If anyone should come to know the Little World properly, then nothing of the Greater World would remain unknown to him … I say to you, my disciples in the study of Nature, if you do not find the thing for which you are seeking, in your own self, much less will you find it outside your self. Understand the glorious strength resident in your own selves. Why trouble to enquire from another? In Man … there are things more glorious than are to be found elsewhere in the whole world. Should anyone desire to become a Master, he will not find a better material for his achievement anywhere than in himself … from an eager heart, moved by my own experience, I will cry out to my beloved fellow men: “Oh! Man, know thyself!” In you resides the Treasure of all Treasures … which by men of experience and intelligence, is named the Great Wonder of the World. It is in reality a burning water, a liquid fire, more potent than all fire, air, earth, or water. In its crude state it dissolves and absorbs solid gold. It reduces it into a fatty blackish or blackish-grey earth, and a thick, slimy, salt water; without fire, or acid, and without any violent reaction, which no other thing in the world can accomplish. Nothing is excluded from it … the Wise Men of old sought for and found it.

Ali Puli continues, elaborating upon this Salt of Nature:

… it is a Spiritual Water, a True Spirit, the Spirit of Life itself … This is the Foundation Stone, in truth, which is rejected by the careless ignorance of the Builders … Friends, I have shown you The Way, and now I will add with more sufficiency: The World containing the highest and most immediate element of the Wise Men for the achievement of the Masterpiece is Man himself … The Ore is the best and also the worst. The most precious, is a most turbid water. These are like Earth and Water, yet neither one nor the other is any good by itself. From these two, a Son, or a Seed, emerges, and from the three bodies [principles], there is formed the Spirit and Soul in Man … If the Artificer could find this … he could then separate the pure from the impure. He could make, without fire and without any extraneous matter, a Virgin Earth, without odour and without colour. He could divide and secure from it: Sal Centrale, Vitriolum Microcosmi, the Venus of the Sages; Sal Astrale; Mercurium Microcosmi, and Lunam Philosophicam [and produce the Philosophers’ Stone]. Once purified, he could produce a Son, better than his parents …

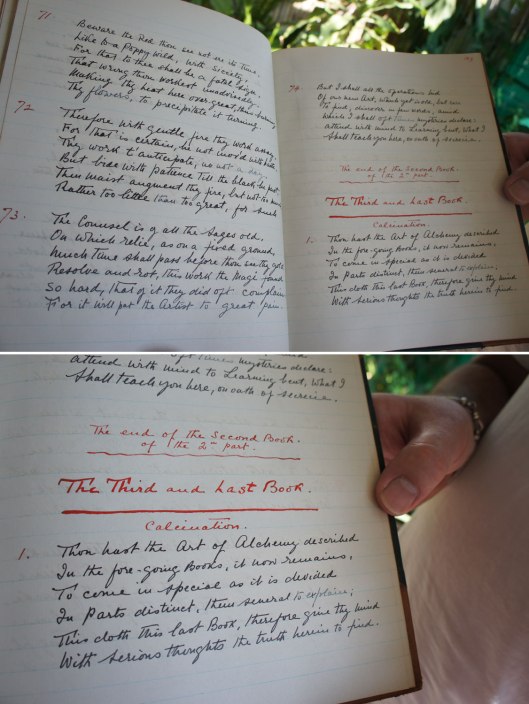

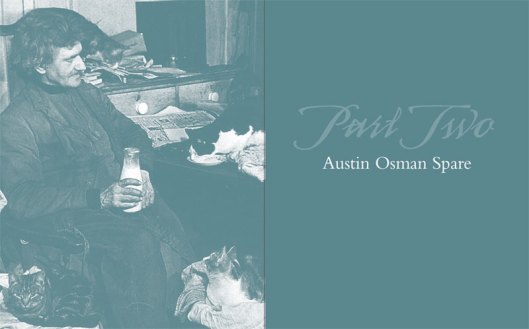

It is worth noting that this second of seven pass-keys – ostensibly comprised of lengthy extracts from the treatise of Ali Puli – bears extensive annotations in the hand of Lapidus. For example, where Ali Puli writes that all metals are born from the very volatile, sweet and sparkling Astral or Uppermost Salt and the Central Salt, the latter of which he describes as “a Vitriol of remarkable and inexpressible strength,” Lapidus has crossed out the word born and written quickened, as in “From these two kinds of Salt, all metals are quickened.” Where Ali Puli writes, “Here you have the Mine, in bodily form; and without any admixture you can make Gold and Silver from Quicksilver, Copper and Lead, etc.” Lapidus has written OR antimony, Mars and Venus, and Secret Fire, as in “… and without any admixture you can make Gold and Silver from antimony, Mars and Venus, and Secret Fire.” Where Ali Puli writes, “First learn Wisdom for the sake of your own soul, and all will be well with you … Wealth untold is brought to you. But first find the Natural Central Seat in Man; then your lawful labours shall prove as successful as you wish,” Lapidus has written Natural Central Salt of Nature beside “Natural Central Seat in Man.”

Throughout the remainder of the second pass-key, Lapidus quotes from the following sections of Centrum naturae concentratum: ‘Of Mercury and Vitriol or Sulphur’, ‘Of Salt’ and ‘Of Colours’.

Ali Puli describes the all-powerful Philosopher’s Mercury as “a true living Mercury, not to be named living, because he becomes a Quick-metal … yet he is living because in him is the living seed of gold; little in weight it may be, but great in vigour, for it can make ordinary fine gold become living gold, and ten or twelve times heavier; it can also expand in a very pervasive way.” He elaborates upon the birth of the living gold via the addition of Vitriol, rightly describing it as “a masterly operation in metallic substances.” This living gold is “capable of being multiplied out of the Mercury and water in the Vitriol, and increasing many hundreds or thousands of times,” and affecting metallic transmutation.

Ali Puli writes:

After maturation, or fixation, as it is now termed, one part of the tincture will transmute ten times more into gold than the tincture from a combination of Mercury and common gold would do … I have made metals to mature through an ingression of Mercury, and this quick-metal, which transmutes into fine gold, i.e. 100 parts of silver into fine gold, or 100 parts of copper into silver, many have called the Sulphur in Mercury, Sophorum or Universal, because they employed it for other uses as a tincture, but they did not know its origin … In order to make common gold pervasive, you must understand that Mercury alone provides the means for ingress for the Vitriol and the Sulphur into metals, and the contraction of this Mercury makes it mature. The moisture of the quick metal passes into the dryness of the Mercury and the whole becomes tincture. There is no such thing as a wet state in the world of Nature. Ignorant folk have understood the word moist to mean wet. A wet state destroys everything. Our water does not wet the hands, but it is moist. The saline liquors have nothing to do with this.

Where Ali Puli writes, “The moisture of the quick metal passes into the dryness of the Mercury and the whole becomes tincture,” Lapidus has written The moisture of the quick metal passes into the dryness of the GOLD, then the whole becomes tincture. Where Ali Puli writes, “There is no such thing as a wet state in the world of Nature,” Lapidus has written There is no such thing as a wet state in the world of metals.

Ali Puli articulates the difference between alchemical dissolution and putrefaction, highlighting that “… all that we therefore perform, happens through the process of a simple dissolution and coagulation; nothing comes about through any process of decay, such as people generally believe to be the case.” He elaborates upon the planting of a seed into soil; that it does not decay but is instead swelled and turned to slime via the vital salt sinking “down into the soil with the dew and the rain penetrating through the shell of the seed into the kernel”; that the vital image of the plant or tree arising from this dissolution eventually acquires an existence “in material form through its own vital salt, vitriol and water” and is coagulated as a result of being “constantly fed by the penetrating vital salt from dew and rain” percolating into the soil. “From this process there grows a large plant or a tall tree, provided the soil remains, wherein the nourishing sal centrale sustains and feeds it.”

Lapidus concludes the second pass-key with this paragraph regarding colours, as put forth by Ali Puli:

When the dissolving process of the gold has been completed and the separation of the water ends, the mass throws off all impure and extinct earth on to the edge of the glass vessel and appears white. Here it is to be noted that the substance does not change in one day, but requires much time, because each colour, in its growth, appears slowly, becomes strong, and gradually shades off. When the white colour begins to appear, the substance gradually turns into a powder … Here the maturing process starts and subsequently proceeds to coagulation (commonly called fixation) and … a further process follows … the longer this process takes the better the result – until at last the small corpuscles become firm and compact, the yellow colour comes along, ending with a red, and our task is finished.

This post is extracted from Paul Hardacre’s 15,000+ word paper, ‘The Lost Book of Lapidus’, presented at the 2012 Esoteric Book Conference in Seattle.

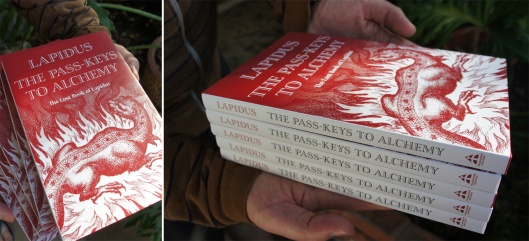

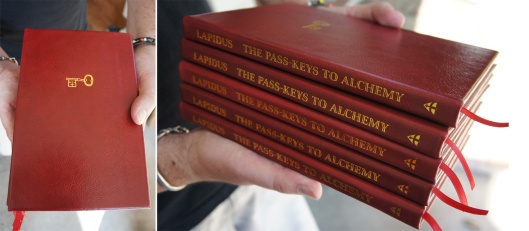

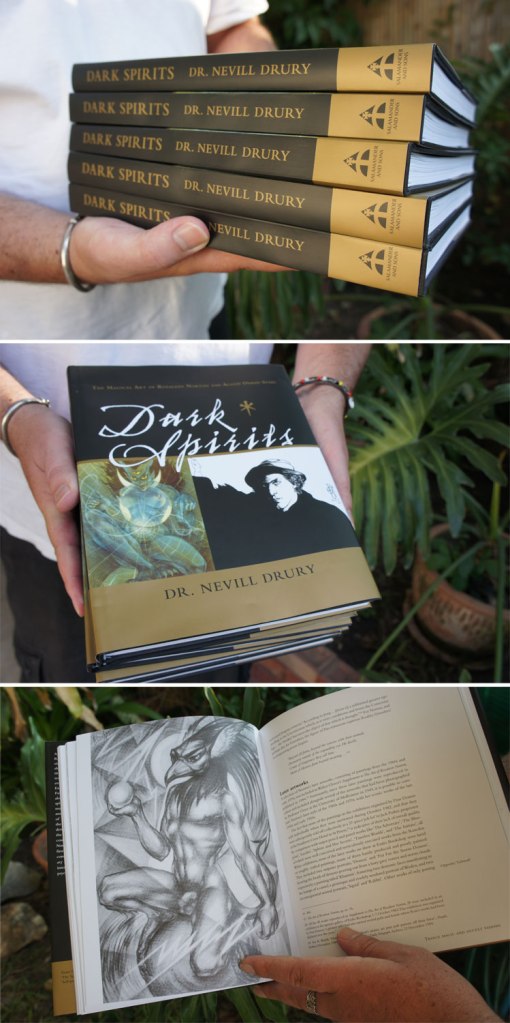

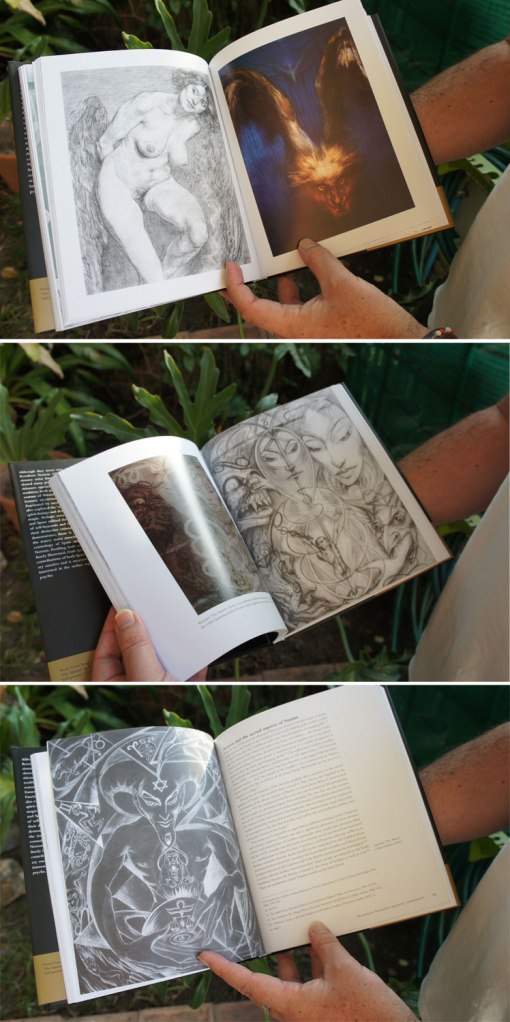

The Pass-Keys to Alchemy is available from Salamander and Sons.